My history with this book is long, drawn-out, and expensive. Given all that, I feel the need to write a proper review, so I at least have something to show for my time and effort.

The history

Sometime between 2000 and 2002, my college pal Dillon screened the anime series Future Boy Conan (1978) for Vassar’s geek club, the NSO. The 26-episode series was Hayao Miyazaki’s directorial debut — before Studio Ghibli was even a thing — and it displays prominently the environmental themes Miyazaki will return to in Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke.

Personally, I quite loved it. And yet, some fifteen years later, my memories are primarily emotional. I resonated strongly with the deep loneliness that Conan feels, and with the sense of a world lost under the rising oceans.

Also it had a pig called Umasou (Looks Delicious). So there’s that.

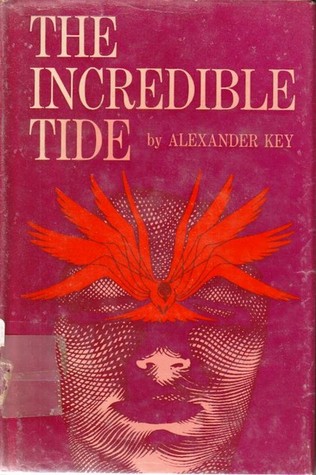

Dillon informed us that it was based on The Incredible Tide (1970), by Alexander Key (who I venture many Americans of my age primarily associate with Escape to Witch Mountain, of which I retain even dimmer memories). He also told us that the book was wildly out of print, and hard to acquire.

Well, of course that only made me want to read it even more.

The “hard to acquire” bit was relevant. This was before the era where ’80s and ’90s kids found their childhood re-released in ebook form. The nostalgia factor was driving prices of this volume up to absurdity in the early 2000s, mostly through Amazon resellers — if you could even find it at all. I was told at one point it had only ever been released as a library edition, further fueling its scarcity.

However, in 2004 I attended the World Science Fiction Convention when it was in Boston, and among many other things, they had a ginormous dealer’s room. Here, at the booth of Somewhere in Time Books, from St. James, NY, I traded $200 for an ultra-rare copy of The Incredible Tide.

Which proceeded to sit on my shelf for over twelve years.

Fast forward to 2017

However! An opportunity presented itself this weekend, when I found myself dog-sick with (what I suspect was probably) norovirus. I wasn’t puking, but I was nauseous and feverish, and my skin hurt. Reading in bed was pretty much all I was capable of. And a book aimed at children/teenagers seemed about all I could handle.

I suppose you should examine this review in that light — I read most of The Incredible Tide while being very ill, and it might have colored my perception. But I emerged from the weekend without hating the Rifftrax Time Chasers coloring book I was working on, or Kevin Hearne’s Hounded, or Tad Williams’ The Dragonbone Chair (both of which I attempted to read, to varying degrees of success), so I really do think it was the book.

Because the book is… well, if the adjective “phoned in” was used in the 1970s, one might say Alexander Key phoned this book in.

Possibly via satellite phone while vacationing on a Caribbean island. Potentially while drunk on pina coladas.

What I’m saying is, the craftsmanship is just sloppy throughout. That’s overall my biggest complaint. Each of the factors I’m about to list, by itself, wouldn’t sink the book; but this general carelessness, on the whole, makes this book less than successful.

Anyway, first things first:

Plot Summary

Conan is a young boy who was abandoned on a little spit of rock when an “incredible tide” covered the world. Somehow he figures out how to survive on that rocky islet, and lives there for five years, until he’s found at the age of seventeen by the “New Order,” a group that is trying to remake the world — with technology!

Not these guys.

That makes them, by this book’s logic, the villains of the piece. In particular here we meet Dr. Manski, who becomes marginally relevant later.

At the same time, we also meet Lanna, far away in High Harbor, a community that was established by “Teacher,” a.k.a Briac Roa, when the world was going to shit. For some reason we are never told, Teacher then got captured by the New Order? But he apparently can stay in psychic contact with his daughter Mazal, whose husband Shann leads High Harbor. (Lanna is their daughter).

But there’s political unrest in High Harbor, as the New Order is trying to take over (via its agent Dyce), and a group of feral teenagers, led by a guy named Orlo, are trying to ally with them.

Pretty much, as far as I can tell, Lanna exists only to tell us this side of the story. And to have a crush on Conan. Her only other defining feature is her awful fear of vast expanses of ocean, which is totally understandable under the circumstances!

Meanwhile, Conan is “rescued” and brought to Industria, the New Order capital. They want to enslave him before he can become a citizen, and are resentful that he doesn’t seem grateful about this. He is imprisoned when he resists being branded by the New Order While imprisoned he discovers that Teacher/Briac Roa is also under the thumb of the New Order, posing as crackpot shipwright (two words I never thought I’d put together) Patch. “Patch” rescues Conan by requesting him as labor for his shipyard, and fills Conan in on his escape plan.

Their escape plan, however, goes awry. Whilst in the middle of robbing a workshop for supplies to escape, Teacher realizes that Industria is going to fall into the sea and decides that informing them of this is The Right Thing to Do ™, Right Now. He sends Conan off on the fragile boat they’ve built, while he risks his life to tell the people who have imprisoned him that he is this Briac Roa they’ve all been looking for, and hey, your city is in danger. This goes over about as well as you might imagine. He survives only because Conan comes back to rescue him.

Together they try to make their way to High Harbor, but are pursued by the New Order. A storm lands them on… the very same island Conan was stuck on for five years! The storm does away with his New Order pursuers, conveniently, except for Dr. Manski, who they just kind of run into on this giant ocean. She argues with Teacher about the existence of God while they wander around in the mists that make this post-apocalyptic sea mostly unnavigable. Finally they are able to make it back to High Harbor thanks to Lanna sending Tikki — the tern that kept watch over Conan through his time on the island — back to find him, conveniently overcoming her terror of the ocean all at one go.

The book ends with the tsunami Teacher has been predicting, which decides to show up just in time to wash away the New Order agent on High Harbor. It would have washed away Orlo, too, except that Conan decides that rescuing him is The Right Thing to Do ™. He is knocked over by the wave, but the people of High Harbor help him to his feet.

The end.

No, really, that’s where it ends. Mid-paragraph, it seems, as if the author just got sick of writing the story. What was the promise of the story, and was it fulfilled by this ending? Who knows…

Element by Element

Writing

The basic writing is bland, but not terrible. I’d call it workmanlike. No beautiful turns of phrase here, but we do get a sense, in the early chapters, of the lay of Conan’s island. It didn’t leave me with that nostalgic yearning for a world lost that Future Boy Conan did, though, but I’m willing to forgive that.

But soon enough we meet people for Conan to interact with. And augh, the dialogue. To say it is a wooden is an insult to hard-working wood. Modern reading preferences favor verisimilitude in speech in fiction; SFF, true, can get away with less. But by whatever standard, no humans anywhere talk like this. The conversations are like summaries of talking points, with many exclamation points. To give you an example, there’s this argument between Dr. Manski and Conan:

“Oh, stop talking like an idiot! Don’t you realize it took both sides to do the damage?”

“I don’t believe it!”

“But it did! Now someone has to put the pieces back together.”

“Only it has to be done your way — and with branded prisoners! You’d even take over High Harbor if you could, and rob everybody of his rights! Why you’re the dirtiest bunch that ever–”

“Shut up!” she ordered icily. “No one has any rights, not even I. Only the state has rights — the New Order. It’s only the state that–”

“State, my eye! Of all the stupid ideas!”

“You’re the stupid one! Stupid and ignorant. Of course we’ll take over High Harbor — and soon! We’ll be doing them a favor. They’re entirely incapable of looking after themselves. If you could only see–”

“I can see how warped and twisted you are! And greedy!”

Some of this might be a function of the characters, who are… well, let’s get to that.

Characterization

… is the biggest weakness of this book. Mostly, I didn’t like any of the characters, and I didn’t care what happened to them. It made reading even this little 153-page volume a real chore.

At the core of it, it’s that they are ciphers, with no internal life; more stand-ins for an ideology than real people with hopes and dreams. Most of the narration is just an action-by-action recitation of what they’re doing; occasionally we get a “this made Conan mad,” but no sense of the context, or how we’re supposed to feel about it. It becomes hard to follow, as a result — a bland landscape without value judgments. An example:

Instantly he began scrambling forward, climbing over the disorder of equipment and groping for the coil of line and the piece of broken concrete that, because of the scarcity of metal, had to serve as an anchor. He found the concrete finally, started to heave it over the bow, but thought better of it and began lowering it carefully. It was well that he did so, for he paid out nearly the entire coil before the line went slack, and when he reached the end he found that it had not been made fast to the cleat on the foredeck.

(Don’t ask me how many times my poor, sick mind had to re-read this paragraph).

Teacher at least SEEMS like he might have internality. He’s literally the world’s smartest man, a shipwright, a seismologist — and, more tellingly, the one “good” character who attempts to understand the New Order point of view. But the author doesn’t want to show us more than just a tease of who he is. Does he think the young minds that are his audience can’t handle the complexities of opposing points of view? I don’t know.

God help you if you are a female character, though. Lanna, Mazal, Dr. Manski all seem to exist to further Conan and Teacher’s plots.

The moments where Conan and Teacher choose to endanger themselves in order to help people they hate is clearly supposed to be characterization. But… it feels pasted on. We can’t predict it from their actions elsewhere. And it ends up feeling as preachy as many things in this book are; like the author is bashing us over the head with THE MESSAGE.

Speaking of which…

THE THEME

As I said, Future Boy Conan has environmental themes. The Incredible Tide has an agenda.

It starts before the book even does, with this dedication: “To a people unknown, of a land long lost — for surely what is written here has happened before. It depends upon us alone whether it is a reflection or a prophecy.”

Well, all right, then.

A few chapters in, I joked to my husband that “so far this book has been Alexander Key’s diatribe against synthetic fabrics,” and it wasn’t far from the truth. Witness these choices tidbits:

Page 29: … he was given clothes to cover his nakedness. They were old and patched, and made of a shoddy synthetic material that felt unpleasant against his skin…

Page 30: “And don’t call the food synthetic. It is the best food ever made, and the most scientific.”

Page 48: But the New Order’s cloth would help. It was sleazy, of course. It was about the worst stuff she’d ever seen. Yet it was better than no cloth at all.

Page 56: It was a pair of sandwiches made of synthetic materials, obviously the product of machines. He thrust the unpalatable things in a corner and reached eagerly for the water bag.

Of course, never is it mentioned that, hey, maybe this is the work of a society attempting to survive in a post-apocalyptic world where wood and metals are rare. Nope, it’s clearly because the New Order are the villains, and therefore anything they do is bad. We should all be pitching in together and “making a game” of survivalism (this is literally how Lanna says High Harbor survives the rough times) and weaving our own wool-linen blend cloth, apparently. (Again, a thing Lanna literally does).

We don’t have much doubt as to the author’s intentions, do we? Throughout, he’s sending a message — synthetic bad. Natural good.

And by “sending” I mean “double ham-fistedly pounding you about the head and shoulders with.”

Did I mention the stuff about the Voice? Apparently if you are a protagonist, or protagonist-adjacent, you hear a voice that tells you the right thing to do at any given time. It helped Conan survive on his island, and it also tells you to do things like continue sailing blindly into the abyss, or to love your neighbor, or whatnot. This is so clearly a god-analogue that even Dr. Manski can sense it, and spends much of the penultimate chapter of the book arguing with Teacher about it.

Even if you’re religious, this is like a four year old’s understanding of God, and feels appallingly simplistic in a book that is ostensibly aimed at much older children.

And now repeat that sentence, replacing “God” with “environmental issues,” and that’s my executive summary of this element of the book.

(Idiot) Plot

The plot is the original idiot plot — driven entirely by convenience and people making really stupid choices. Some examples:

Conan apparently could have avoided capture by the New Order by fleeing to the eastern islet of his archipelago. He didn’t.

Conan could have apparently just punched out the door of his New Order prison, because it’s made of plastic. (And as we all know, plastic is an evil — and thus inherently flawed — synthetic). But he doesn’t, until he’s nearly dying of thirst, at which point Teacher convinces him not to, because… they are being watched?

Industria has been in danger from earthquakes and tsunamis since it was founded — and Teacher, theoretically, knows that — but he decides, at the moment when he and Conan are about to make their triumphant escape, to inform the authorities of this?

(In retrospect, it occurs to me that he might have seen signs that there was a recent tectonic shift, which might make the threat more imminent. But from the reader’s perspective, all we know is that Conan has a sense of dread, Teacher stops and examines a crack on the floor, and then, suddenly, they call the whole thing off. My primary reaction was largely, “huh?”, which is probably not the response the author wanted to this dramatic reveal. Again this may be largely a function of Teacher being, like every character, a cipher).

Teacher is blind. Not that this is ever relevant, because he is apparently strong in the Force, and can sense things regardless, up to and including the position of a compass needle. (No lie, he’s framed as being able to sense the world via some semi-magical, sensory-compensation-gone-wild kind of thing). It ends up feeling like Key just sorta forgot he was blind throughout half the book, so made up an explanation that he thought sounded good. (It didn’t).

How the heck does Conan ever end up on the island by himself? It’s implied that he was escaping with Teacher and Lanna before the apocalypse, and that Lanna had enough time to gift him with Tikki, but that’s about it. Why isn’t he at High Harbor with the rest of them? Did they have to drop him as ballast or something?

If Lanna is a gifted psychic communicator, why hasn’t she communicated with Conan during the FIVE YEARS they were separated? Eventually she uses that ability, together with Tikki, to bring him back to High Harbor — which only begs the question of why she didn’t do this earlier. You might be forgiven for thinking it’s her agoraphobia — the view of the vast ocean she sees whenever she ascends to the watchtower on High Harbor sickens her. But she doesn’t need to be there to communicate, as is made clear later in the book. At that point, it’s literally explained to us as, “she tried it once as a kid, and it decided it didn’t seem like something she should be able to do, so she never tried again.” Which seems merely engineered to give us the central plot complication.

The other thing I have to say about the plot is — what is it? Everybody just seems to be reacting to events around them. There’s no through-line, no drive forward, which in most modern fiction comes from the main character’s wants and needs. Conan never seems to want or need much beyond what is in front of him. As an example, he’s only escaping Industria and heading for High Harbor because it’s what Teacher wanted. We have a general idea it’s a thing he wants, too, because we know NEW ORDER BAD, but it doesn’t feel real or complex.

Still not these guys.

This is what I meant when I asked, “what is the promise of the book, and does the ending fulfill it?” I don’t know, because I literally don’t know what the plot of the book is. The end feels abrupt because we don’t know if we’ve arrived — because it’s never clear what the destination should be.

Again it ends up feeling more like ideology than story. It makes a little sense if Teacher and Conan are ciphers for Hope, Youth, Age, Wisdom, Harmony, etc, and High Harbor is some sort of Promised Land, but if these are real characters? It all falls apart.

And personally, I was hoping for characters, and a story.

Random Creepiness

I could have done with Orlo’s clearly (to an adult mind) rapey intentions towards Lanna. Witness:

“An’ do you know what Orlo an’ the commissioner plan to do?”

“What, Jimsy?”

“Take over your house. Doc an’ his wife, they gotta move. But Orlo says he’ll make you stay. That’s how he figgers on getting even for what you done.”

Wtf? I mean, YA these days tangles with some tough topics, but this childish explanation of what is basically SEXUAL ASSAULT just feels so off-the-cuff and unnecessary.

(I also would like to point out: if we’re supposed to accept High Harbor as this standard of community living in harmony with nature, then how the hell are we supposed to reckon the feral teenagers it has apparently produced?)

“Do you want feral teenagers? Because that’s how you get feral teenagers.”

Also strange and hard to explain is how everyone seems to fetishize Conan’s body, like he’s sooooo healthy and toned by living alone on an island and doing physical labor for five years. Multiple examples like this exist in the book:

Page 10: He sighed and stood up, rubbing his calloused hands over his very lean and very hard body.

Page: 29: “I’d hate to see such a fine young body thrown away. Such beautiful muscles! In all my life I’ve never seen their equal.” She felt his arms. “Like steel! The New Order needs your strength.”

Page 33: “But he’s amazing! Such health! Come here, young fellow,” the commissioner ordered, “and let’s have a look at you!”

What Age Range is this Even For?

The breakdown of middle grade/YA is a very modern one, so in general I’m okay with it being vague in books that pre-date that distinction. I recently re-read one of John Bellairs’ Johnny Dixon books, and was able to say, “hey, this is clearly middle grade, even if no one would have called it that at the time.” In many ways that’s a good comparison — they were shelved in the same place in my elementary school library, and the authors were rough contemporaries.

There is no such tell here. If you go by the age of the protagonist, The Incredible Tide is YA. But the reading level is… let’s generously say, it’s below middle grade. It’s certainly not as complex as some of the beautiful MG we have today (take the first Harry Potter novel as an example, or my pal Django Wexler’s The Forbidden Library). It reads as even more simplified than the John Bellairs.

And of course there’s the weird skirting of much more adult topics, which I don’t know how to categorize. One of my favorite YA novels (Laini Taylor’s Daughter of Smoke and Bone) opens with a frank discussion of penises. Contrast this with MG, where there seems to be a strict “no kissing” rule — a minor crush is about as much you can show. Again, this book is not consistent with either standard.

The overall effect, then, is that Key is talking down — and quite condescendingly — to his audience. Which is like no-no number one of writing for a young audience.

In Conclusion

In general I felt like this was a manuscript, not a book. It falls prey to common pitfalls of inexperienced writers — mostly around giving us characters to empathize with, and not forcing a point of view down the reader’s throat. (And yet, this is his TWELFTH novel). I’m not sure why an editor didn’t catch any of this, but it does not, ultimately, feel like a book that could be published today.

But who am I kidding. Really, this book failed because it didn’t have a porcine character named Looks Delicious.

And with that, I can confidently say I wrapped this review up more satisfactorily than the book itself did.

If, after reading this review, you feel the incomprehensible need to read the book, fear not! The ebook is free with Kindle Unlimited ($5.38 otherwise). Makes me even more bitter about how much I spent…